‘Vaderland’

UCT Hiddingh Gallery, Cape Town.

Up until 1994, almost all able-bodied white male South Africans were called up for National Service around the time of leaving high school. As far as most of these young men were concerned, there was little option but to perform this duty. One’s call-up could be deferred for a few years if one studied, but to avoid it meant facing harsh consequences.

During their period of service the majority of conscripts underwent intense physical, skills and weapons training, with many being sent to fight South Africa’s war in northern South West Africa and Angola or deployed in South Africa’s black townships during the late 1980s. Whilst some conscripts served reluctanly with little enthusiasm, the vast majority of men served willingly, believing that they were fighting pro patria and shielding South Africa from the rooi/swart gevaar – the supposed conterminous threat of communism and Black Nationalism.

But in 1994, when political power was transferred from the white minority to the black majority, ex-servicemen found themselves in an ideologically transformed country. The so-called “terrorists” were recast as heroic “freedom fighters” and soldiers, who belived strongly that they were upholding Christian values against the godless communist onslaught were stigmatised as the evil military agents of the apartheid state: verkrampte zealots defending the indefensible.

The exhibition Vaderland is concerened with the complexities involved in remebering the “Border War” and those who faught in it.

DADDY LAND

Exhibition Text by Chad Rossouw

I remember having a braai at my father’s house when I was a laaitjie. He had a guest over, a neighbour. As they had both been in the army, and the company was all men and sons, the conversation naturally turned to military experiences. The neighbour spoke of his experiences on the border (my father hadn’t seen active service). It has stuck in my mind, perhaps because it was my first experience of male bonding, or because I felt included at a time when my father’s house and my mother’s house weren’t the same place. Either way, there was a sense of pleasure in meat and conversation, army experiences and neighbourliness.

Years later, I realized that the Border War wasn’t a nice war, that the group Koevoet that he served with was not neighbourly, and that driving around with a black man strapped to the grill of your Casspir is not a story but an atrocity.

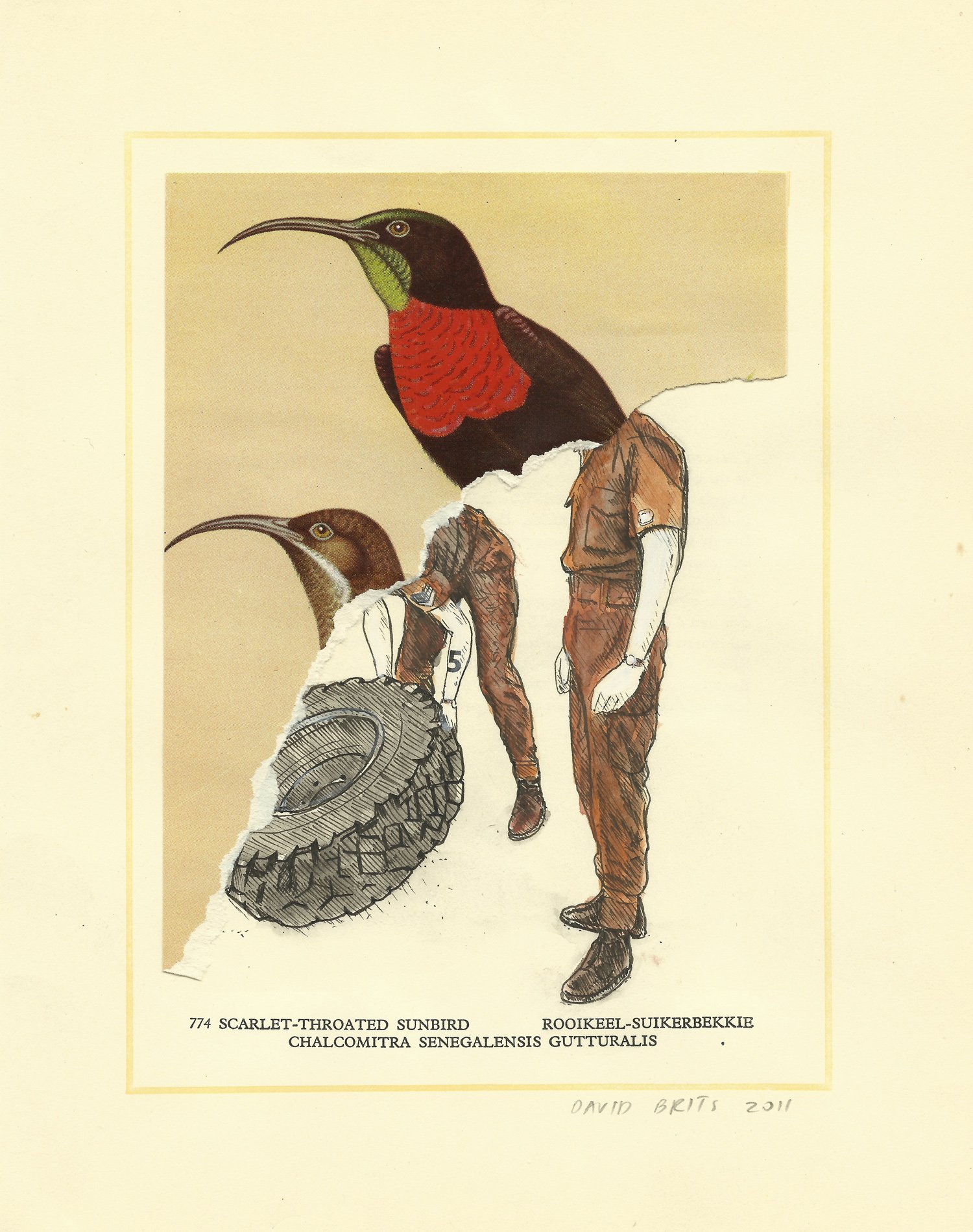

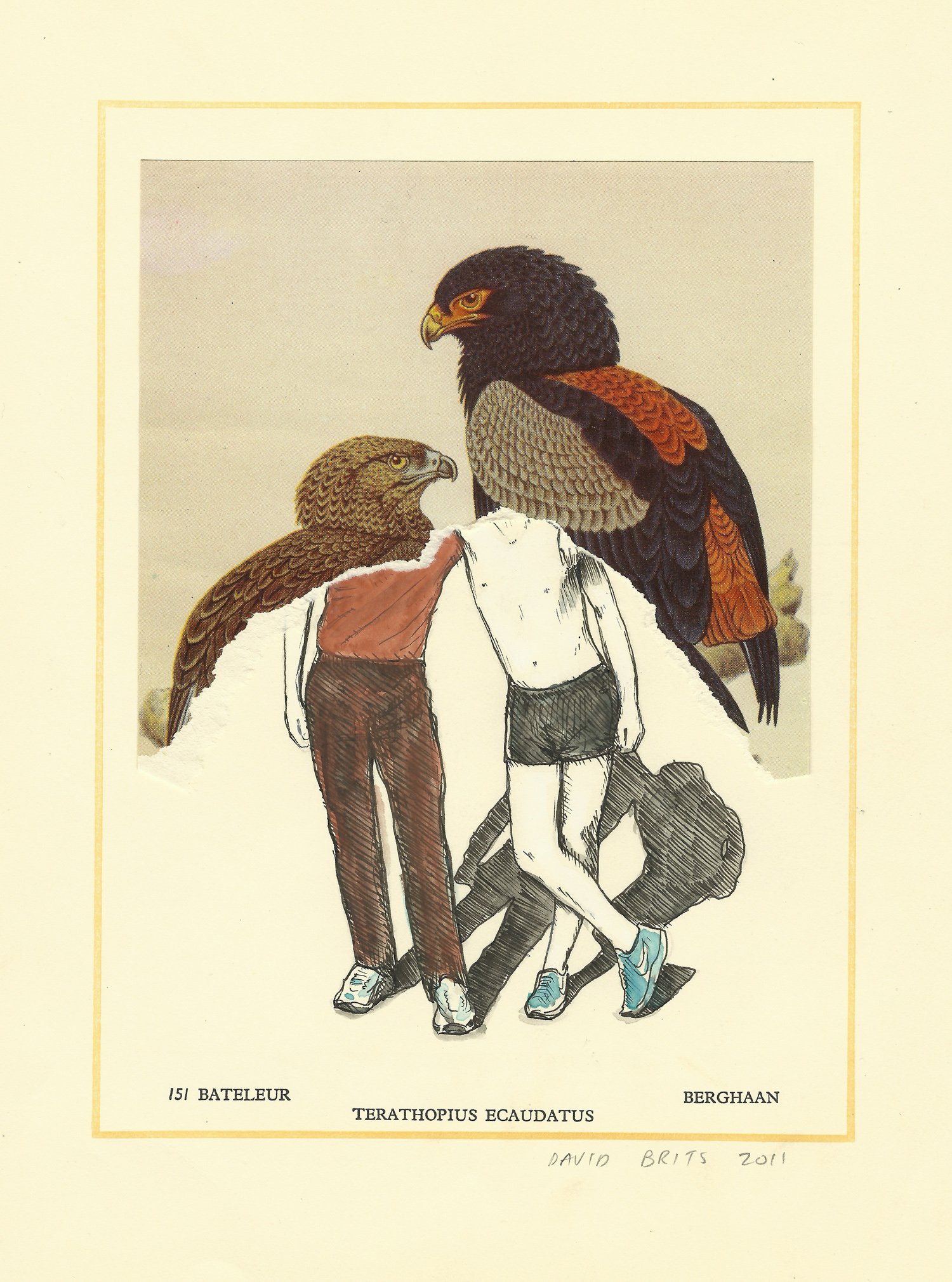

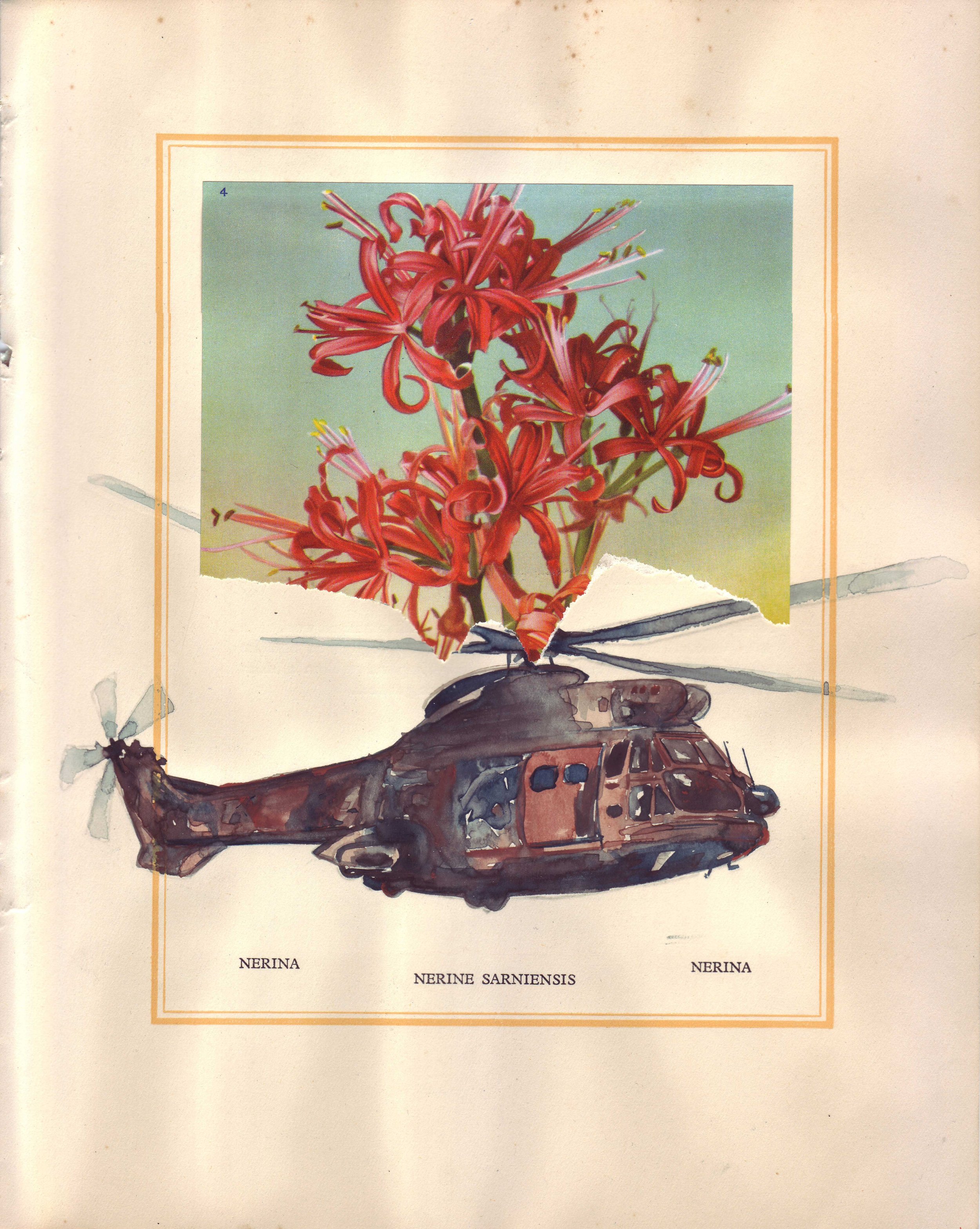

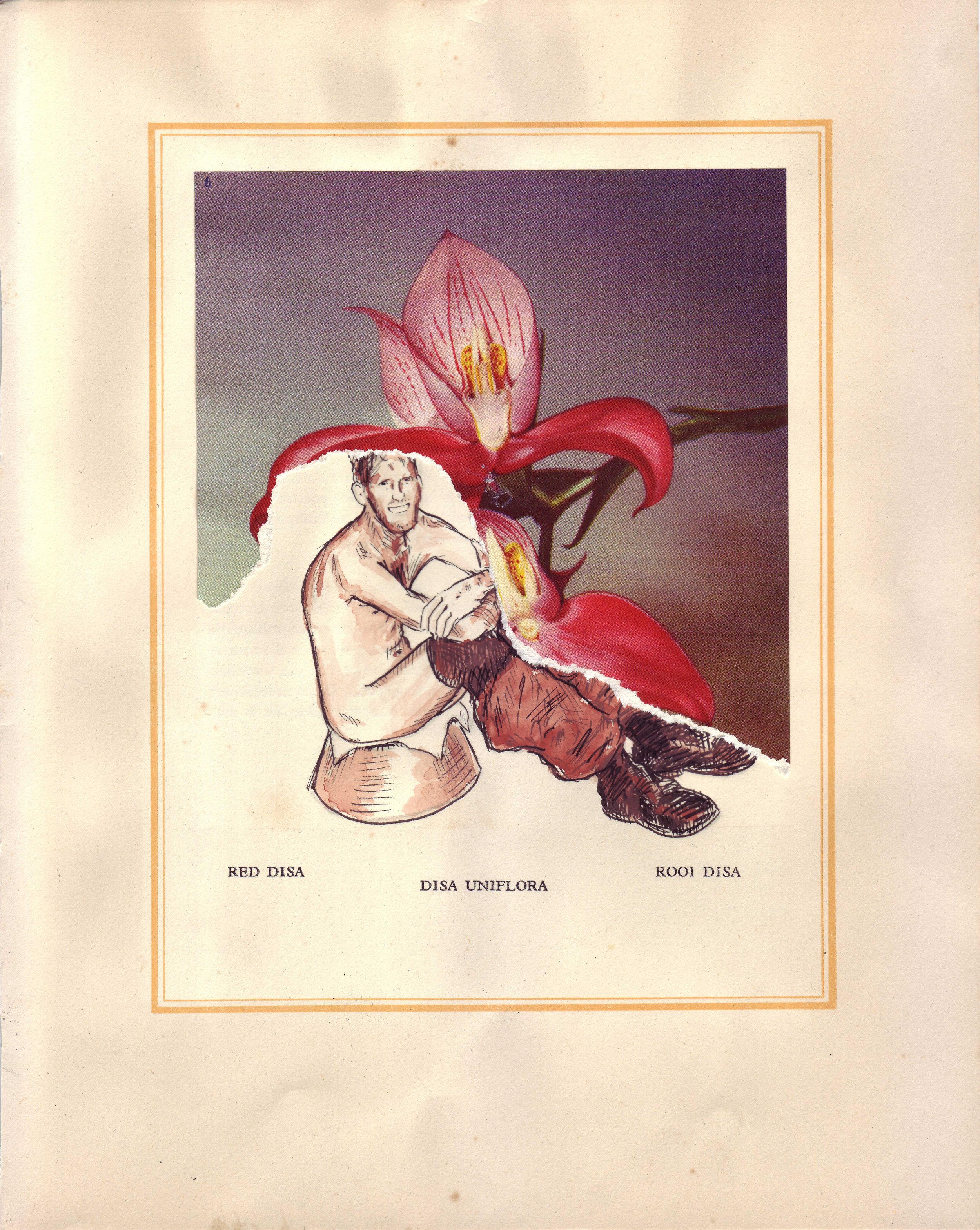

There’s a peculiar dislocation between my nostalgic recollection of a time of masculine bonhomie and my own experiences of South Africa. It is somewhere in this sense of dislocation that I would locate David Brits’ Vaderland. While David’s work never veers into personal narrative territory, there’s a clear sense of nostalgia in his material, faded photographs and yellowed paper. But this longing (or even sensual pleasure) for the old is always tempered. There’s an element that jars, something is displaced or juxtaposed which skews the easy feeling. In a series of collages on vintage paper, drawings of South African soldiers are half obscured by torn images from natural history collections. A man’s legs hang out from underneath a protea. While at first this is a visually strange combination, the intersection between the military’s defence of the land and the myth of an Arcadian land of nature to be categorized and admired has its own logic. Both images are ideological, the army as the visible might that upholds the system, while the impulse to collect natural history implies a sense of ownership of the land. This connection doesn’t allow either image to settle.

A second series of drawings adds another complex element. On a similar collection of pages from a natural history book, crude handwriting delineates bald statements that David associates with the Apartheid army (“fokken moffie,” “bosbefok,” etc). There’s a similar juxtaposition to the flower series, but the act of writing is both imaginative and performative. David has to imagine the mind of a soldier from a different generation. In writing it down, he has to enact the character. The crooked handwriting implies an anger which doesn’t relate to David. He wasn’t there, he’s not this person. He is performing a gender role which is affirmative, replicating our fathers’ masculinity, but also critical and ironic, in its need to take on a performed, imagined and essentially distanced form.

From Border War photos nicked from Facebook, to helmets gushing black cloth this complex interaction between gender, nostalgia, criticality and politics plays itself out within this show. But at its heart, it’s Luke and Vader, the big theme of masculine production: the classic daddy issue, both wanting and rejecting the love of a father.

SELECTED WORKS:

1979 (2010) Ink and Gouache on Found Object. 20x35cm

Vlag (Vaalkombers) (2010). Stormy Blanket, Thread. 1.2x1.7m

Vlag (Browns) (2010) Apartheid-Era Army Uniforms. 1.2x1.7m

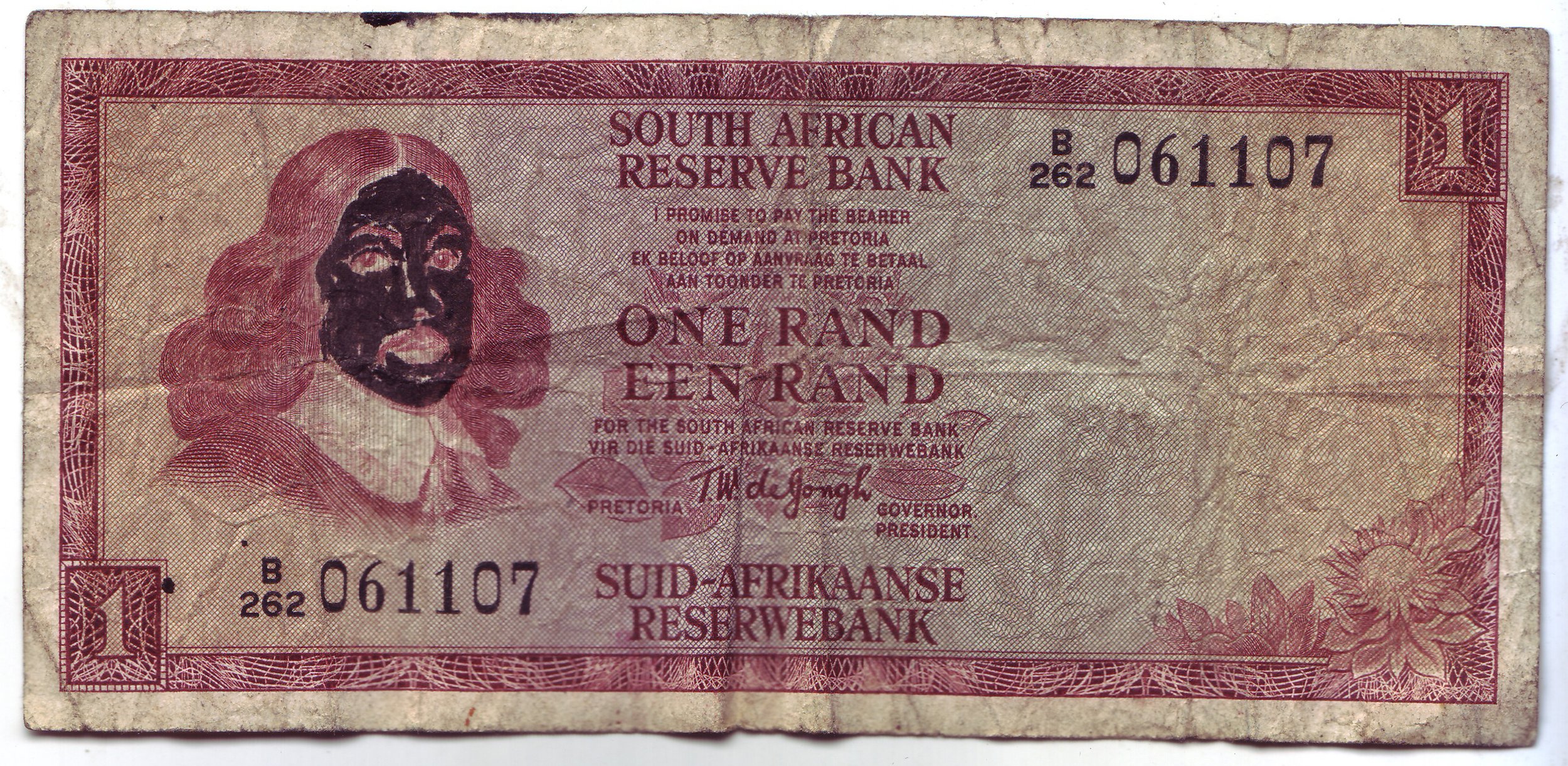

Jan 2 (2010) Indian Ink on decommissioned South African banknote. 9x12cm

I Know What I Like (2010) Gouache on Found Object. 21x30cm

Jan (2010) Blood & Banknote on Found Object. 21x30cm

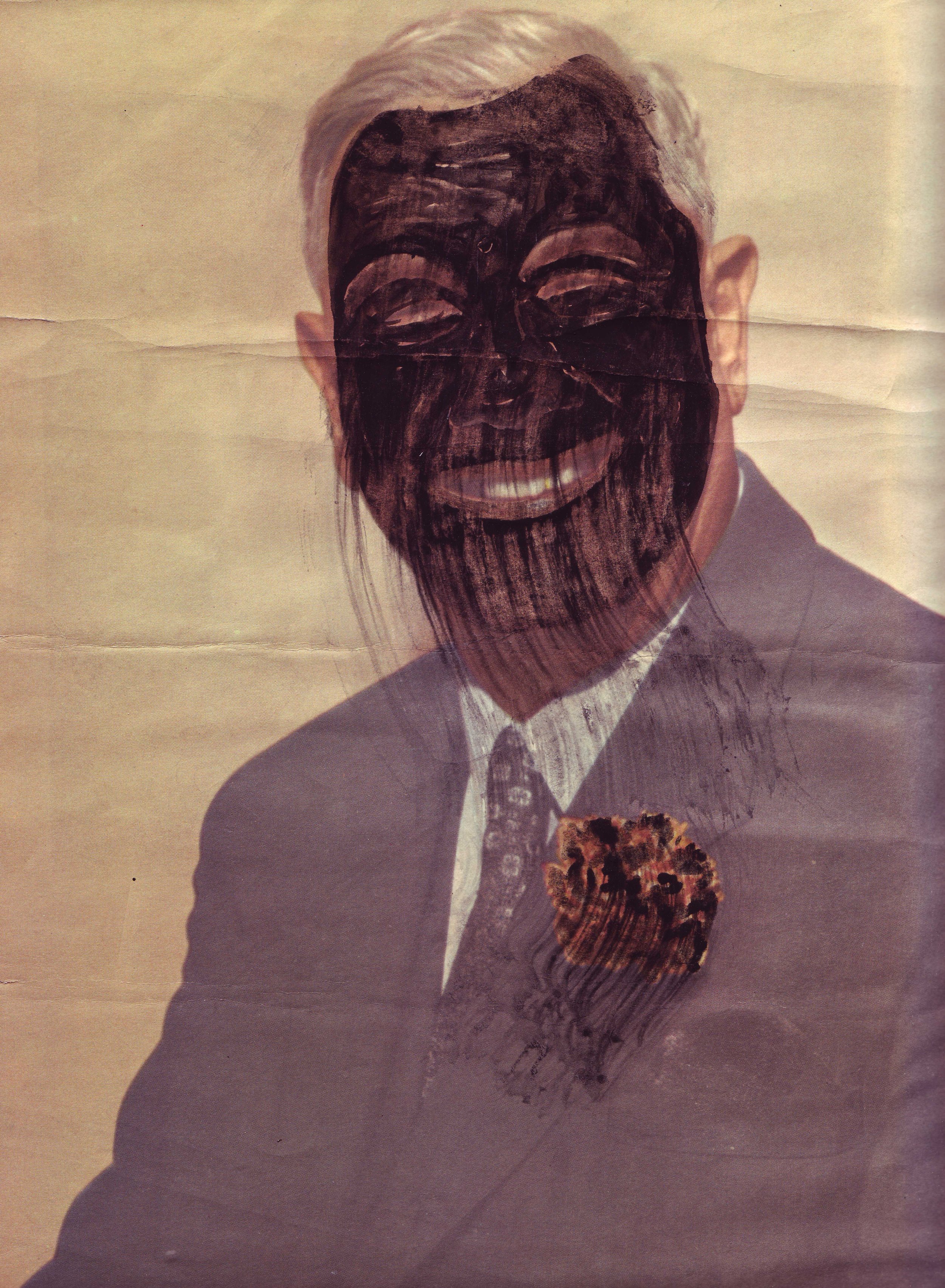

Blackface (Verwoerd) (2010) Gouache on Found Object. 21x30cm

Vark (2010) Bitumen and Gold Leaf on Found Object. 12x18cm

Blackface (Panga) (2010) Ink and Gouache on Found Object. 21x30cm

Man The Fuck Up (2010) Reverse Acetone Print on Fabriano Academia. 12x20cm

Country of my Skull (2010) Indian Inkand Guache on Postcard. 10x18cm

Scarlet-Throated Sunbird (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Bateleur (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Tropical Ruddy Waxbill (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Kalkoentjie (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Nerina (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Sour Figs (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Red Disa (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Giant Protea (2010). Ink And Gouache On Found Object. 18x27cm

Forget Your Border War

An Essay by David Brits

SOLDIER SOLDIER

I was born on the 23rd of September 1987, at ten past six on a bright spring morning in Mowbray Hospital’s maternity ward. The next day, in the bed alongside mine, another baby boy, Mark Vallance was born. Mark and I grew up being best friends. For fun we would dress up and play games like Cops and Robbers, Cowboys and Indians, and, our favourite War. One day, Mark’s mom hauled out his dad’s old army kit bag down from the attic for us to play with. I remember how the army uniforms and kit had a sickly smell and were stiff and dull brown with age and lack of use. To our excitement in the deep brown bag, we also found a small square of camouflage netting and a poncho – perfect materials for us to build our very own army ‘base’ in Mark’s garden. We worked hard all morning, finishing construction on the base just in time for lunch. That afternoon it began to rain. Pretending to be soldiers, and with his dad’s oversized army gear on, Mark and I crouched underneath the cramped tent with warm cups of Milo and high expectations of being kept dry. But our base was no match for the winter drizzle – the tent soon leaked and we both got wet.

It was not uncommon for people like Mark’s dad, like my dad, and most of my friend’s fathers’ for that matter to have their army kit in their attics. Like most men their age, shortly after they finished high school our fathers were conscripted into the South African Defence Force (SADF). Most were put through rigorous physical and skills training and many were sent to fight in South Africa’s so-called “Border War” in Northern South West Africa and Southern Angola.

But since the radical shift in political power in 1994, the “Border War” and those who fought it have been cast in an insidious light. From an institutional point of view the conflict is now widely regarded as one which upheld the racist interests of Apartheid, and the soldiers whose lives were lost while fighting in it not worthy of commemoration. The “Border War”, it would seem has become ‘officially’ forgotten in post-Apartheid South Africa.

WHAT IT MEANT TO BE A CONSCRIPT

“Are you fuken mad? Are you going to wait until you are standing with your back to South Beach before you realise that the communists plan to take over your country? This is the thin edge of the wedge, pally. If we lose the war up here, we’ll be overrun. The blacks will take over… and that will be that.”

– A Sergeant Major to Rick Andrew. (Andrew. 2001: 73)

Up until 1994, almost all able-bodied white male South Africans were called up for National Service around the year they turned 18 (Thompson, 2006: vii). As far as most of these young men were concerned, there was little option but to perform this duty. One’s call-up could be deferred for a few years if one studied (Thompson, 2006: vii), but to avoid it meant facing harsh consequences. The options were to object on conscientious or religious grounds and face a six year jail term, or flee the country (Baines, 2008a: 1).

During their period of service the majority of conscripts underwent intense physical, skills and weapons training (Thompson, 2006: vii). Commonly known as basics, this was a mandatory period of around three months, where troops would be trained in any number of roles – from army chefs to Special Forces – deployed in and around South Africa and serving in a variety of capacities in the Air Force, Navy or Army.

The SADF gradually extended the period of military service from nine months to two years (Baines, 2008a: 1) to meet the military’s escalating demands for manpower. And for men like my dad, one’s obligation did not end with the two year national service. After their initial tour of duty conscripts were assigned to citizen-force or commando units and were subject to such periodical call-ups, or “camps”. These usually lasted three months and involved physical and skills training as well as possible deployment in military “operational areas” (Baines, 2008a: 1). I remember my father telling me how up until the age of thirty he’d have to haul his kit bag or balsak from the attic, squeeze into his old uniform and go on a “camp”. Each year he had to take off work and perform duties such as guarding the Naval Headquarters at Silvermine, and in the 1980s, a time which saw a rapid escalation of township violence, he was even retrained in urban warfare and riot control. According to historian Gary Baines, most in “Dad’s Army” – as older servicemen were often called – remained part-time soldiers for most of their adult lives (2008a: 1).

From 1974 tours of duty in “operational areas” included being sent to fight South Africa’s war in northern South West Africa and Angola (Thompson, 2006: vii) or being deployed in South Africa’s black townships to curb civil unrest from 1984 (Baines, 2008a: 1).

According to Baines the term “Border War” or “Bush War” was usually assigned to the war waged in Angola/South West Africa (David Bunn holds that quotation marks are necessary because Angola does not share a border with South Africa (Bunn, 1998: 59)) but this conflict was actually an extension of the civil war waged within South Africa to the wider region. Sporadic and related skirmishes against Anti-SADF forces occurred throughout Southern Africa in places such as Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe (former Rhodesia), Mozambique, Lesotho, Swaziland, former Homelands within the current South Africa; and South Africa itself (‘Bush Wars – South African Angolan Conflict’, 2006). According to Baines the term “Border War” was ubiquitous in white South African public discourse during the 1970s and 1980s… As a social construct, it encoded the views of (most) whites who believed the apartheid regime’s rhetoric that the SADF was shielding its citizens from the “rooi/swart gevaar”; the supposed coterminous threat of communism and Black Nationalism. (Baines, 2008a: 1)

Writer Paul Hopkins sharply points out that the overriding fear for the founding fathers of the National Party was the swamping of the volk by other races. Hopkins explains, “that when the party came into power in 1948, it wasted little time in enacting legislation to classify and separate various [race] groups” (Hopkins. 2003: 32). And to enforce their racist legislation and apartheid laws, the government required effective, dominant and –most-importantly – feared security and military forces. The writer Gary Zukav argues that this is because the police and the military reflect the way that we have come to view power both as a species and as individuals:

Police departments, like the military, are produced by the perception of power as external. Badges, boots, rank, radio, uniform, weapons, and armour are symbols of fear. Those who wear them are fearful. They fear to engage the world without defences. Those who encounter these symbols are fearful. They fear the power that these symbols represent, or they fear those whom they expect this power to contain, or they fear both. (1990: 7)

In a country where “the power to control the environment and those in it appeared essential” (Zukav, 1990: 7), for whites, it was vital that the militarization of South African society under apartheid became, as Baines describes it, “comprehensive” (2008b: 215). The conscription of young men into the armed forces era enabled the military domination of the black majority upheld by Apartheid’s laws, thus ensuring political control for the country’s four million whites.

AN UNPOPULAR WAR?

I don’t want no teenage whore

I just want my R4

I want to go into Angola

I want to kill a SWAPO soldier

If I die in the combat zone

Box me up and take me home

Pin my medals on my chest

Tell my mom I’ve done my best.

- Marching song of 8 SAI, the 8th South African Infantry Unit

But since the conflict ended in 1989 and conscription was subsequently phased out, time out of uniform has given ex-combatants time and distance to reflect on their experiences of the “Border War”. Within the changing political landscape to which they have had to adjust, they have done so in a number of different ways, one by “inserting themselves into the history of the “Border War” on the printed page”(Baines, 2008a: 2).

JH Thomson’s book, An Unpopular War: From Afkak to Bosbefok (2006) is a compilation of interviews the writer held with ex-servicemen of the South African Defence Force (SADF). Thomson interviewed over forty men “in order to record their personal memories of this military era,” documenting their experiences of inspections, training, covert operations, camp life, drinking, fighting, patrols, secret operations and open combat. The preface describes the book as a “collection of mental snapshots from their time as SADF conscripts” (vii).

Baines notes that although Thomson’s book has been very popular (it has undergone six reprints and translated into Afrikaans), he argues that the author chose an inappropriate title. Baines holds that the “Border War” was never unpopular amongst the majority of conscripts nor was it frowned upon by the white populace at large – rather it was often seen as a rite of passage into (white) male hood (Baines, 2008b; 215), and an essential commitment to make in order to ensure the continuation of white power and privilege (2008a: 5) – views reinforced by social institutions such as the family, education system, mainstream media and the churches. (Baines, 2008b; 215)

TURNING THE TABLES

“If one person’s “terrorist” is another’s “freedom fighter”, then South Africa’s white minority’s “Border War” was the black majority’s “liberation struggle”.

(Baines, 2008: 1)

But the decade of the nineties saw dramatic changes taking place in South Africa. With the voting in of South Africa’s first ANC-lead democratic government in 1994, a radical shift in political power occurred. van der Watt notes that “after almost three-and-a-half centuries of colonial domination and four decades of apartheid governance, political power was finally transferred into the hands of the previously oppressed and disenfranchised majority” (2003: 1).

The racial ‘borders’ and divisions that the Apartheid regime and its military machine fought so hard to enforce suddenly dissolved. South African society became porous (although not necessarily homogenous) as these borders dissolved both nationally – the Bantustans were dismantled – and internationally – Namibia became independent in 1990 after being a South African protectorate since World War II.

With this shift in power against the background of the changing political landscape to which they have had to adjust, ex-SADF servicemen found themselves having to make sense of the time they spent in uniform (Baines, 2008a: 5). Having had both time and distance to reassess their experiences on the “Border” Baines observes that in retrospect, “widespread moral ambiguity” has been conferred on the war by white South Africans (Baines, 2008a: 5).

Commenting on this phenomenon art critic Lloyd Pollak writes that the South African forces fighting on the “border” “believed, or tried to believe, that they were fighting pro patria, upholding Christian values against the godless communist onslaught” (2010: 8). But in 1994, when political power was transferred from the white minority to the black majority, the tables were turned. Ex-servicemen found themselves in “an ideologically transformed country in which the “terrorists” were recast as heroic “freedom fighters”” (Pollak, 2010: 8). Within this new political environment, demobilised soldiers who felt that they had fought so hard and sacrificed so much for their country were stigmatised as “verkrampte zealots defending the indefensible” (Pollak, 2010: 8).

FORGETTING THE BORDER WAR

“For now it’s as if there is this tacit, silent agreement between the two sides not to speak about it. To just rather not go there… in the interests of keeping the peace”

– Willem Steenkamp, ex-SADF conscript and author of three works on South Africa’s “Border War” (de Beer, 2005: 36)

In creating the ‘new’ South Africa, the period after 1994 saw the ANC-led democratic government undertake the massive task of bringing the people of a radically polarised country together. To effect desperately needed unity among a racially and economically, historically and ideologically, linguistically and culturally divided nation a radical wave of “nation-building” took place. Mechanisms and ideas of ‘inclusively’ and ‘unity’ were employed to create a sense of much-needed national “togetherness”. Desmond Tutu christened the newly democratic country the “Rainbow Nation” – a term which transformed South Africa into a country in which all people could belong. However, historian Edward Renan that such strategies of uniting and including people are in forming a nation:

Inheritance in the ‘new’ South Africa may be understood to be linked with a mourning which is doubled against expectation of restitution and repossession, As much as this is a cultured climate of remembrance, it is equally a time of strategic amnesia. (Renan, 1990: 11)

But just as it was important to remember and celebrate points of commonality among South Africans as a means to bring the populace together, equally it was vital to forget the events and factors which shaped the country’s segregation. According to Renan “forgetting, I would even go as far as to say historical error, is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation (1990: 11). During the time of democratic change, Ingrid de Kock wrote that “it is understandable for a country in a historical moment such as this to attempt to erase the fouler accretions of its past” (Law. 2002: 38). Thus the “Border War” becomes a case in point.

In the ‘new’ South Africa it would seem that the “Border War” has been viewed as one such “fouler accretion of the past” – a war to uphold the “privilege and power” of the white minority and ensure the continuation of Apartheid. It is in this way perhaps, Gary Baines is incorrect in his observations that the title JH Thomson’s collection of memories by ex-servicemen, An Unpopular War is inappropriate after all. For although the “Border War” was never unpopular amongst the majority of conscripts or the white populace at large, to call it ‘unpopular’ in within the ‘new’ South Africa would be an understatement.

In the instance of South Africa’s involvement in Angola, the democratic ANC government has made no moves to commemorate a war (or those SADF conscripts killed fighting in it) that was directed under the auspices of the apartheid government (de Beer, 2005: 36). In a paper titled Finding Angola, Sara de Beer deduces that this is tantamount to making a decision to forget. The “Border War”, she says, “has been excluded from official commemoration because it exists as a stain.” According to de Beer “it has no place in the ‘new South Africa’ (2005: 36). She offers a possible reason why in the following paragraph:

Against a democratic South African government that advocates “national unity” and a spirit of forgiveness, stands the potentially divisive fact of South Africa’s involvement in the Angolan War. Thabo Mbeki, when deputy president of South Africa, said in his “I am an African” speech, “…it seems to have happened that we looked at ourselves and said that the time had come for us to make a superhuman effort… to respond to the call to create for ourselves a glorious future, to remind ourselves of the Latin saying: Gloria est consequenda- glory must be sought.” Angola, the unglorious war, does not fit into that construction of South Africa. (de Beer, 2005: 37)

CONCLUSION

“I penetrated a place that existed only in the memory of others

My return was painful, marked by memories I had not lived through.

A part of me has been mutilated, amputated.”

– Zinganheca Kutzinga, in an excerpt from the memórias íntimas marcas exhibition catalogue (1999: 40)

I was born on the 23rd of September 1987, at ten past six on a bright spring morning in Mowbray Hospital’s maternity ward. I was born at the time when the “Border War” was simultaneously at its height and demise. For thousands of kilometres away, unbeknownst to my family, one of the “Border War’s” biggest and most decisive battles – the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale – was taking place in a small town in south-eastern Angola. A few years later, my best friend Mark and I built an army tent in the garden with his father’s army kit down from the attic. It began to rain and our shelter leaked.

Although I was born at the height of Apartheid, I was far too young to experience it directly. Too young to understand a monolithic, invisible, sense of Apartheid-era whiteness which for centuries seemed so rooted in common sense thought. Too young to remember saying goodbye to my dad each year when was called up to do military “camp”, training to fight the “communist terrorists” on the “border”.

But then when I was finally old enough to experience such things, something happened – Apartheid came to its bitter end. In the period after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, whites were thrust from their seat of centuries-old political and hegemonic power to the periphery, becoming an ethnic category in crisis. Apartheid’s “fouler accretions” along with the conflicts and individuals that upheld it – the “Border War”, SADF conscripts – came to be viewed in a sinister light. Swiftly the conflict was swept under the historical carpet and the “Border War” was ‘officially forgotten’.

SOURCES

Andrew, R. Buried In The Sky. Kwazulu-Natal: Penguin Books. P 79.

Baines, 2008a. ‘Coming to Terms with the “Border War” in Post-Apartheid South Africa’. In National Arts Festival Winter School Lecture, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 1 July 2008. P, 1. Retrieved on 10 July 1010 from http//:www.rhodes.ac.za/edu/baines.winterschoollecture.htm

Baines, 2008b. ‘Blame, Shame or Reaffirmation? White Conscripts Reassess the Meaning of the “Border War” in Post-Apartheid South Africa.’ In Interculture [Online] P 215. Retrieved on 11 July from http//:www.rhodes.ac.za./edu/baines.blameshameorreaffirmation.htm

Bunn, D. 1998. ‘Gavin Younge’s Distant Catastrophes’. In Arnott, B (ed.) Staff Of Michaelis School of Fine Art Work in Progress. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. Pgs 58, 59.

‘Bush Wars - South African-Angolan Conflict 1966-1989.’ 2006. In Bush Wars Conflict – Mod for Modern Assault [Online]. Retrieved on 13 June from http//:www.bushwarsmod.net/info.htm

de Beer, S. 2005. ‘Finding Angola’. Honours Thesis in South African History, University of Cape Town. P 36, 37.

de Kock, I. 2002. Cited in Law, J. ‘The Full Catastrophe’. In Penny Siopis: Sympathetic Magic. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. P 38

Hopkins, P. 2003. Cringe, the beloved country. Cape Town: Zebra Press. P 32

Kutzinga, Z. 1999. ‘Blending Emotions.’ In Kellner, C (ed.) Marcas News Europe No4 Brussels: Sussuta Boé. P 40.

Pollak, L. 2010. ‘Ways of Seeing at ORE Gallery’ in The South African Art Times. July edition. P 8.

Renan, E.1990. ‘What is a Nation?. In Nation and Narration (ed. Bhabha, H. K.). London: Routledge. P 11

Thomson, J.H. 2006. An Unpopular War: From Afkak to Bosbefok. Cape Town: Zebra Press. P vii.

van der Watt, L. 2003. The Many Hearts of Whiteness: Dis/Investigating in Whiteness Through South African Visual Culture. PhD Dissertation. P 1.

Zukav, G. 1990. The Seat of the Soul. Parktown: Random House. P 7.

Vandag, Môre, Altyd Saam (2010). Tryptic. Archival Print. Each 15x30cm